The history of factoring can be traced back thousands of years. However, arrangements that benefitted business owners or entrepreneurs in the days of trading grain are much different than what helps people in cash economies today. Factoring has evolved with the times too.

This page will walk you through the full timeline of factoring history, including its origins, how it evolved, and how it works today.

Invoice Factoring Definition

The word “factor” comes from “factus,” which means “done” or “made” in Latin. “Factor,” therefore, loosely translates to “doer” or “maker.” This is likely a nod to trade enablement. A factor is a person or organization that facilitates business activities, generally by providing resources.

Modern invoice factoring is a financial transaction in which a business sells its receivables to a factor at a discount in exchange for immediate cash. It’s differs from a loan because the business isn’t expected to pay back the money. Instead, the business’s customer clears the debt by remitting payment to the factor for the invoice.

Factoring in the Ancient World (3100 BCE – 539 BCE)

It’s often said that the first civilizations on earth were involved in factoring. This isn’t necessarily true, but the economic developments they made and the way they engaged in trade laid the groundwork for a variety of systems that evolved into the trade, banking, and financing systems we have today.

The Phoenicians (1550 BCE to 300 BCE)

Most people trace the history of factoring back to the Phoenicians, a group of people who lived in what’s now parts of Lebanon and Syria. To give some context, these people initially lived in very small groups, were spread out, and mostly survived on farming. They didn’t engage much with outsiders or trade. However, the communities were close-knit. If someone needed something and another person had it, it was generally freely given or lent. The concepts of credit or interest didn’t really exist.

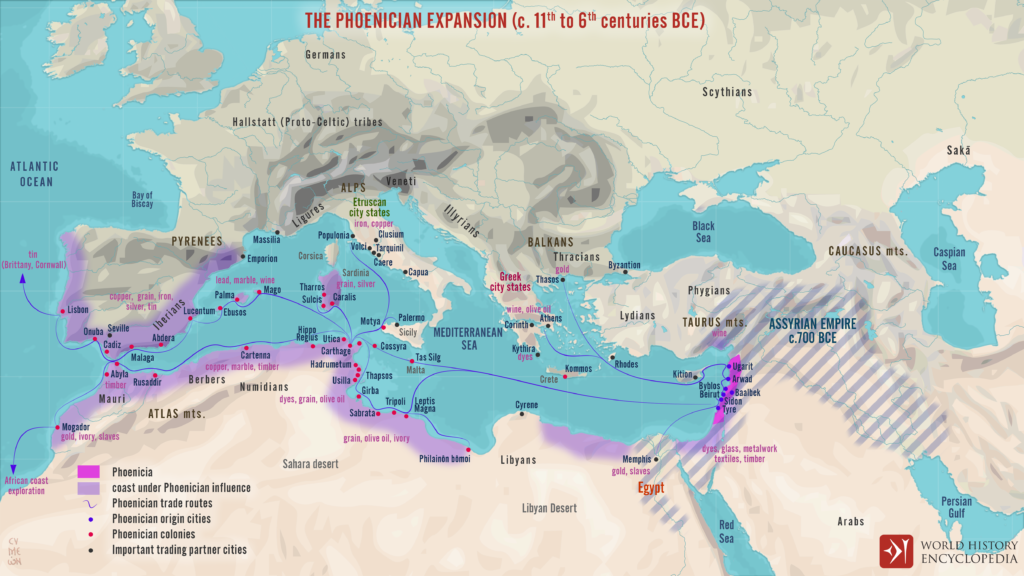

As Assyria expanded and took more land, these neighboring communities were pushed to the Mediterranean coastline. The area wasn’t suitable for farming, so the people took to the sea. In this sense, the Phoenicians were never a single unified society. “Phoenicia” was more of an alliance between the people of city-states such as Tyre, Byblos, Beirut, and Sidon, as Khan Academy explains.

The Phoenicians were primarily known for possessing a unique purple dye that they made from snails, which they traded all along the Mediterranean coast. In their travels, they also picked up metals, papyrus, wood, glass, textiles, and carved ivory, which they’d then carry with them and trade at their next stop.

This presented new challenges because prior groups didn’t readily trade with strangers. The states stepped in to regulate trade as a result. Prices, quantities, and exchange rates were all determined in advance per the World History Encyclopedia, and most trading took place in state-sanctioned trade centers. Credit was rarely extended. People typically traded items of equal value or paid on receipt of goods.

“The Phoenician Expansion c. 11th to 6th centuries BCE” by Simeon Netchev CC BY 4.0.

Mesopotamia (3100 BCE to 539 BCE)

Ancient Mesopotamia, which flourished from roughly 3100 BC to 539 BCE and sat in present-day Iraq and parts of Syria, is responsible for several developments in trade and credit that influence modern-day factoring too.

Sumer (4100 BCE to 1750 BCE)

Often referred to as “the cradle of civilization,” Sumer was situated in the southern part of Mesopotamia and existed from roughly 4100 BCE to 1750 BCE. The first mention of interest-bearing commercial and farm debts can be traced to the region, according to economist Michael Hudson, PhD. However, Hudson doesn’t think that Sumerians actually created the concept. Instead, he credits the Phoenicians for bringing it with them on their travels.

Whereas the Phoenicians traded in state-sanctioned trade centers, Sumerians usually traded in local temples. These temples were finance hubs and managed lending too. Sometimes nobility would be involved in trade and lending as well.

Babylon (2000 BCE to 540 BCE)

Situated in the central-southern region of Mesopotamia in what’s now Iraq, Babylon flourished from roughly 2000 BCE to 540 BCE, eventually overtaking Sumer as the center of Mesopotamian activity. This is where we start to see trade and financing in a way that more closely resembles modern factoring.

For example, Babylonian society largely ran on grain, but people didn’t carry grain around in their pockets to make purchases and only used coins some of the time, as Hudson explains in “Handbook of the History of Money and Currency.” People who ran the alehouses would have consignments advanced to them throughout the crop year, and those visiting the alehouses would run up tabs. When harvest time came, the customers would pay their tabs in grain. Those running the alehouses would then deliver most of the grain to the palace as repayment.

Similar arrangements were seen with merchants. However, in this era, merchants weren’t quite like they are today. They were called “tamkarum,” as Cem Eke explains in “The Roles of the Merchant in Ancient Babylon.” Rather than simply trading, tamkarum held high-status positions in society and often represented the palace. For example, they were responsible for documenting trades, which would then be reported to the palace for taxation purposes. They were also among the first bankers. They decided who was credit-worthy and how much credit could be extended, then also lent the money. Because the concept of collateral didn’t exist, some consider the tamkarum to be the first investors too. They had to be very careful about who received their funds.

Additionally, the tamkarum are often seen as the first factors due to their involvement in purchasing receivables. If a Babylonian fell behind on paying rent for his land to the palace, the tamkarum would purchase the debt from the palace at a discount. The palace usually received about two-thirds of the value, and the tenant would then be responsible for paying the tamkarum back.

Tamkarum also hired commission agents to travel to other cities and purchase goods. The agents would bring the goods back and the tamkarum would resell them at a profit. To facilitate this, the tamkarum would make a cash advance to the agent. The agent was then responsible for documenting the agreement and giving the receipt to the tamkarum. Whoever held the receipt was entitled to the goods being purchased by the agent, so the receipts were sometimes sold at a discount as well.

Hammurabi’s Code (c. 1780 BCE)

These transactions set the stage for Hammurabi’s Code, which lists some of the earliest laws on record. Estimated to be drafted around 1700 BCE at the direction of King Hammurabi, the stone etchings contain 282 statutes that cover everything from penalties for causing physical harm to trade and finance laws. One such statute notes:

“If a merchant gives to an agent grain, wool, oil, or goods of any kind with which to trade, the agent shall write down the value and return the money to the merchant. The agent shall take a sealed receipt for the money which he gives to the merchant.”

This law covers the type of arrangement the tamkarum had with their agents and paved the way for modern laws relating to funding documentation.

Ancient Greece and Rome (753 BCE to 476 CE)

The people of ancient Greece and Rome also traded with the Phoenicians, referring to them as the “traders in purple” or “purple people” due to their famed dye. It’s not surprising, then, that ancient Greeks and Romans picked up many of the finance and trading behaviors that were common in the era too.

A veritable treasure trove of Roman promissory notes unearthed in London in 2014, with some dating back as far as 57 CE, is a prime example. Written in Latin cursive on a wooden tablet that was originally covered in beeswax, one reads: “I, Tibullus, the freedman of Venustus have written and say that I owe Gratus, the freedman of Spurius, 105 denarii from the price of merchandise which has been sold and delivered …” as reported by National Geographic.

It’s often thought that these Greek and Roman promissory notes were bought and sold at a discount, similar to Sumerian tamkarum behavior, and much like modern factors. They typically managed banking-type affairs within temples too.

During this era, we also see the emergence of “bottomry,” a method of funding for merchant travel. The borrower could get upfront cash before the ship departed and was expected to repay funds after the goods were sold. If the sales were inadequate, the ship would then be turned over to the investors. If the ship didn’t reach its intended destination, the debt was forgiven. There are clear parallels between this and modern factoring, though historians also believe this is how insurance got its start.

In ancient Rome, societas began forming too. These can be likened to modern corporations, as Peter Temin explains in “The Roman Market Economy;” though the intent was to pool resources that could fund maritime activities. Cato, for example, provided one-fifteenth of the funding necessary for a group of 50 ships. It’s often believed that a similar funding method enabled Claudius to construct the Ostia harbor in 42 CE as well. Being the “gateway to ancient Rome,” the port was vital in the transport of goods, but sandbars prevented larger ships from passing through. Julius Caesar and Augustus both wanted to remedy this, but neither could find a way to address costs, the Colosseo Collection explains.

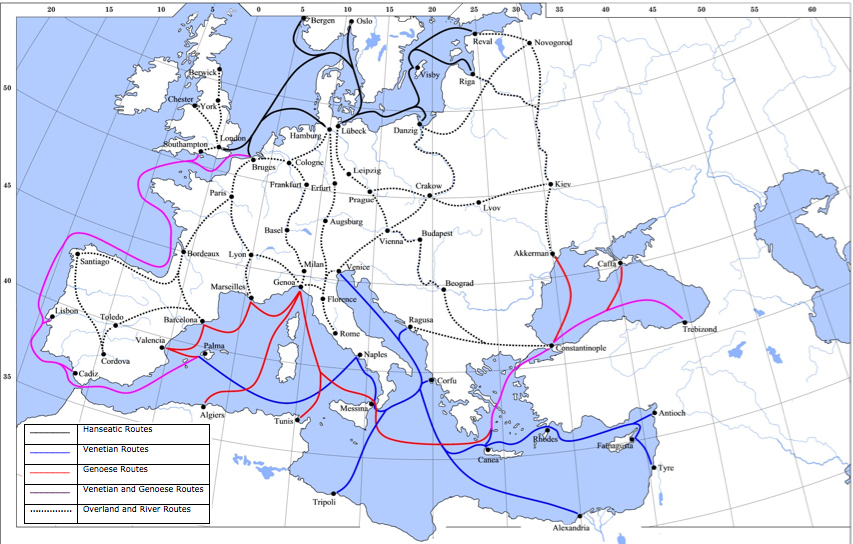

Factoring in Europe (1200 CE to 1820 CE)

Trade in Europe in the early middle ages didn’t drastically differ from that seen with the Romans, as explained by World History. The financial systems were quite similar too, though Temin notes that Amsterdam and London were the most advanced at the time. In these regions, merchants provided purchasers and suppliers with financing without the involvement of third parties. However, it was somewhat common to sell the promissory note locally. “A bill obligatory could be sold to a third person in England,” he explains, “but it did not travel far because it had to come back to the borrower for payment.”

It’s only as we move into the late medieval era that trade dramatically expands, and with it came new ways to finance it.

Italy and France (c. 1200 CE)

In the ancient world, receipts and promissory notes served as funding agreements between two people. These were sometimes bought and sold at a discount, similar to factoring. Whoever held the note or receipt was owed the debt. Moving into the medieval era, that was not always the case. Those extending credit began authorizing others to collect on their behalf. That is a trait shared with modern invoice factoring too, as businesses grant the factor permission to collect an invoice’s value from their client as payment. One of the earliest records of this is a document from 1248, as shared by The Journal of Political Economy:

“I, Aubertus Acua, citizen of Marseilles, constitute you, Dodonus Baldissonus, as my present, certain, and special agent, to demand, collect, and recover from Ricavus Pisanus, a citizen of Marseilles, 250 byzants of Acre which he is under obligation to pay unto me…”

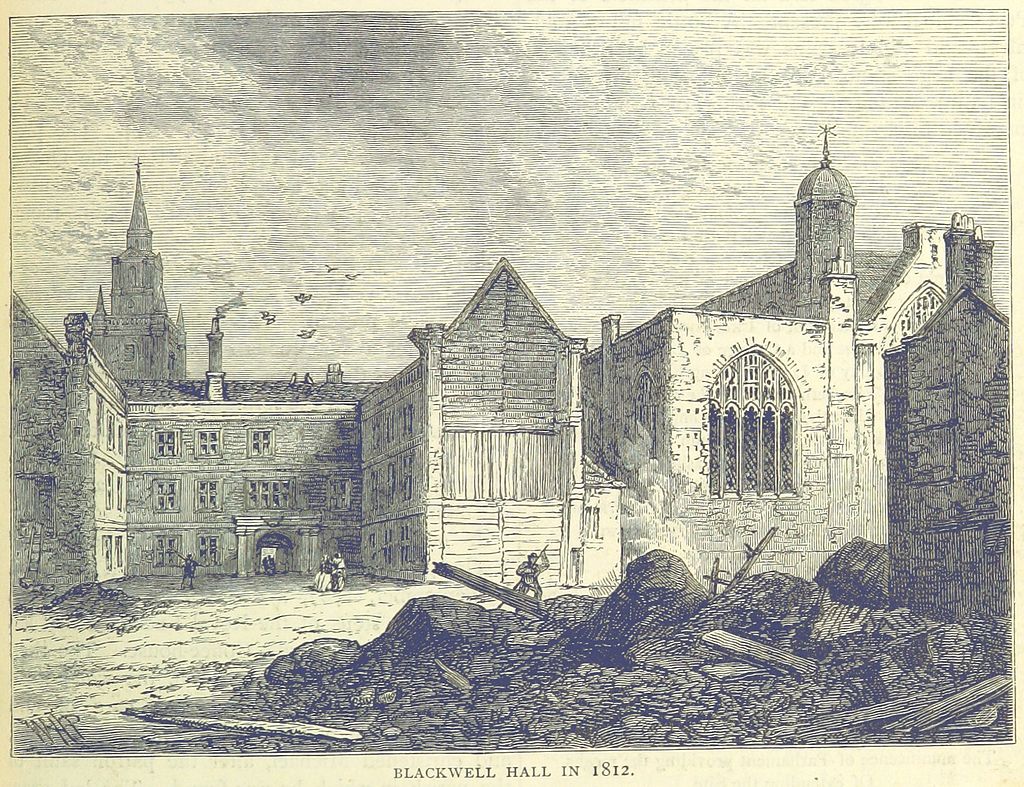

England – Blackwell Hall (c. 1397 CE to 1820 CE)

Up until this point in the history of factoring, the word “factor” was not used as it relates to trade or funding. That changes as we move into medieval England with the introduction of the Blackwell factors.

Established in the 14th century and lasting through the 18th, Blackwell Hall was the center of the woolen cloth trade in London. The marketplace gave non-citizen and foreign cloth manufacturers and clothiers the opportunity to display and sell their material to merchants and drapers. Blackwell Hall factors played a crucial role in the process by finding a market for the cloth, supplying the raw wool, and providing credit that allowed the manufacturers and clothiers to operate, as explained by Conrad Gill in “Blackwell Hall Factors.”

England – Maritime Trading (1450 CE to 1789 CE)

International travel and trade became more common throughout the late medieval and early modern eras. Just as prospectors headed west en masse during the American gold rush, much of Europe wanted to claim a share of the riches being discovered in India. In this case, however, the bounty was spices, cotton, and silk.

Trading posts sprung up across Europe during this period, starting around the mid-1300s. Typically built with the permission of local governments with the intent to trade with natives, these establishments were referred to as “factories.” They’re a large part of the reason why trading companies like the East India Company and the Hudson Bay Trading Company boomed during the era.

East India Company’s first factory was established in 1611 in the Indian city of Masulipatam, according to TutorialsPoint. Thereafter, each factory created followed the same structure as follows per East India Company factory records:

- The company would choose a location for a factory; typically an area already known for commerce.

- A ship would visit and leave behind a chief factor and council of factors to build relationships with the natives and get set up.

In other words, a factory might start out as a warehouse or market, then eventually grow into a defensible post for exploration, and ultimately serve as a governmental head for the local community. A factor, in this sense, wasn’t just a funding specialist. He was responsible for the goods and maintaining order.

The Columbus Voyage Debate (1492)

It’s often taken as a fact that Christopher Columbus’ voyage to America was paid for by factors. It makes sense given that factors or factoring-like activity routinely funded maritime activities during the period. However, these claims are unsubstantiated, and it’s important to remember that the initial voyage was more exploratory in nature. Columbus was trying to find a more efficient route to India and wanted to earn a bounty for being the first to spot land, as explained in “Columbus’s First Voyage: Profit Or Loss From A Historical Accountant’s Perspective.” The first trip was not a financial success.

What we do know is that Columbus put a 12.5 percent stake in the venture, and the Spanish crown funded the remaining portion. This included providing the ships, of which two were taken from Palos as a penalty for alleged piracy. This means Columbus could not have worked out a traditional bottomry deal as he didn’t have a claim to the ships. He was also without money, as the crown was covering his living expenses for years prior to the voyage. It’s likely he took out a traditional loan to cover his 12.5 percent share of costs.

The throne was also short on cash at the time due to recent wars. Many contend that Queen Isabella used the crown jewels as collateral, but this, too, is unsubstantiated. As shown in the profit and loss document, Luis de Santangel helped make the connection. He was treasurer to both the king and the Santa Hermandad. The crown borrowed its portion from the Santa Hermandad under a two-year loan with 14 percent interest. Most sources agree that this loan was paid off much earlier. Given the crown’s financial status, it’s assumed multiple government agencies floated the money until the balance was paid.

Factoring in Colonial North America (1492 CE to 1763 CE)

Maritime activity played a role in the expansion of knowledge and customs throughout the history of factoring. This was shown in ancient times, first with the Phoenicians, then later, with the Greeks and Romans. It’s not surprising, then, that the earliest settlers in America brought factoring with them to the new world too.

Plymouth Colony (1620 CE to 1691 CE)

The Plymouth Colony is often credited as being the first settlement in America funded by factoring. Indeed, it was quite similar. Capital for the Mayflower’s voyage and subsequent settlement was raised by a group of 70 merchant adventurers from London, as PBS News Hour explains. By their account, the pilgrims were in debt, expected to send furs and other goods back to London as repayment.

Additionally, the pilgrims agreed to a seven-year labor contract with the merchant adventurers and were guaranteed equity in the company, according to Yahoo Finance. This makes the situation unique. They were treated like employees, yet they were also governed by a setup like earlier factory systems. In a way, they were like shareholders too.

At the same time, there’s evidence to suggest that many of the earliest investors didn’t stick with the company. Instead, lean times resulted in a reorganization, according to Mayflower History. Just four investors stayed on and, along with a group of leading Plymouth colonists, bought out the remaining investors. No documents related to the deal or structure are available, so this could have been handled like a shareholder buyout or similar to the way Greeks and Romans bought and sold promissory notes at a discount—a precursor to modern factoring.

Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630 CE to 1691 CE)

Settlers in Massachusetts had similar arrangements. “Merchants and financiers in colonial Massachusetts engaged in continuing shifting partnerships that expired after a voyage,” explains Peter Temin in “The Roman Market Economy.” However, he notes that this was on a much smaller scale than what was seen in Plymouth or Rome; none had anywhere near 50 ships or investors.

York Factory (1684 CE to 1957 CE)

Trading companies had a comparable approach in Canada too. Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), for example, established York Factory on the southwestern shore of Hudson Bay in Manitoba. This was a unique factory because it was only accessible by sea and eventually grew into a large, fortified complex with numerous buildings.

The factory enabled HBC to manage business dealings with natives and was used heavily for fur trading. The French and English battled over the complex repeatedly throughout the late 1600s and early 1700s. It was ultimately returned to British control in 1713, at which time HBC again began using it as a headquarters. It remained in operation until 1957. The site still exists and is operated by Parks Canada today.

United States Fur Factory System (1795 CE to 1822 CE)

Columbus and some of the earliest settlers made a point of befriending native people. “I gave them many beautiful and pleasing things, which I had brought with me, for no return whatever, in order to win their affection,” Columbus explained in a 1493 letter to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella. He went so far as to forbid his men from trading things of little or no value in pursuit of building rapport.

Because of this, Native American nations often had stronger ties with those representing various crowns than they did with local settlers. Adding to this, early colonists did not necessarily take the same approach to trading. The fraud and unfair practices of some traders caused distrust between the settlers and native people. Yet, developing and maintaining good relationships was crucial to Americans following the Revolutionary War.

George Washington, the first president of the United States, had previously been a British colonial officer. He understood the advantages and drawbacks of British trade practices very well, and knew that building better relationships with native nations hinged on developing better trade practices. As such, he proposed America’s federal factory system in 1795, the Encyclopedia of United States Indian Policy and Law explains.

The factory system had many commonalities with the financial and trade systems that came before it. For example, a “factory” was akin to a trading post or marketplace and run by the government, similar to the way Blackwell Hall operated. Whereas Blackwell Hall was largely dedicated to wool, American factories were dedicated to the fur trade, like York Factory in Canada was. Moreover, all policies and prices were set by the government, a process that can be traced back to the Phoenicians.

The operational hierarchy was similar to previous establishments too. Each factory was headed up by a factor who was appointed to the position by the president. A factor was expected to track and report all money, goods, and furs that passed through the factory and report it to the government. No personal trading was allowed.

However, the American factory system was unique in that it was not run for profit. Washington set it up purely to nurture relationships with Native Americans, and it worked. After the initial two-year run, the factory system was renewed repeatedly, ultimately remaining in operation for nearly 30 years.

Factoring in Modern America (c. 1800 CE to 1900 CE)

Factoring carried many of these common traits into the modern era. For example, a factor was someone who held and advanced against consigned inventory for a merchant. Most of these arrangements involved distant merchants, especially those overseas. The factor guaranteed the collection of local sales and, as such, accepted a certain degree of risk. Because of this, the merchant would only advance 50 to 70 percent of the inventory’s value.

McKinley Tariff (1890 CE)

The Tariff Act of 1890, also known as the McKinley Tariff, resulted in some dramatic changes. It was designed to protect domestic industries from foreign competition and raised the average duty on imports to almost 50 percent, as explained by House of Representatives research. This naturally reduced demand for factoring services involving consignment among foreign merchants. It also changed the sales process in America, as local manufacturers began selling on their own more. Rising to meet the needs of this new market, factors left the consignment business and, instead, focused on purchasing and advancing against receivables. At this stage, factors also moved from primarily supporting the textiles industry to supporting a variety of industries.

Assignment of Claims Act (1940 CE)

Thus far in the history of factoring, a business could only offer a claim to its receivables for private and corporate agreements. Assignment of claims against the government was banned, as explained by the University of Chicago Law Review. In other words, a business could sell its invoices or borrow against them in many situations, but it could not do so if its client was a government agency.

Because small businesses have historically been seen as more risky borrowers and thus have reduced access to credit, the policy made it difficult for them to bid on and accept government contracts. This also hindered the government’s ability to ramp up for World War II.

The Assignment of Claims Act of 1940 lifted the ban, making it easier for small businesses to obtain the working capital necessary to accept government defense contracts. Many believe this change in legislation funded the war efforts. The law remains in effect today, giving more small businesses the opportunity to accept government contracts.

The Changing Face of a Factor (1920 CE to 2000 CE)

Up until this point, factors were primarily individuals, small groups of people pooling resources, or individuals representing the interest of trading companies. These new laws and economic changes resulting from the Wall Street Crash of 1929 gave rise to the factor as a financial company.

Initially, asset-based lenders began acquiring smaller factors. By the mid-1940s, banks, such as the First National Bank of Boston, also began offering factoring to their clients. Moving into the 1960s, the American style of factoring made its way back to England. This spurred even more banks to begin offering factoring and acquiring factoring companies over the next few decades.

By the end of the 21st century, more small factoring companies began springing up. Oftentimes, these had a boutique-like appeal and catered to a specific industry. For example, Viva specializes in transportation factoring, as well as oilfield, construction, manufacturing, healthcare, and more.

Invoice Factoring Today

These days, banks tend to favor working capital solutions like traditional loans, lines of credit, and credit cards. They’re more long-term solutions with greater payouts and less risk, but they also tend to be inaccessible to small businesses due to credit concerns, time in business, and other rigid requirements.

Thankfully, independent factors like Viva still exist and can purchase invoices from businesses at a discount while providing the business with immediate cash. Most businesses qualify for this service even if they don’t qualify for loans because it’s ultimately the customer that pays the balance.

The process is modernized too. For example, businesses that work with a factor like Viva can get approved very quickly, submit invoices for factoring online, and even get paid on the day an invoice is submitted with a transfer directly into their bank account.

A modern factor can also be very instrumental in a business’s growth by offering insights and additional resources, as well as by providing additional forms of funding as business needs change.

Connect with Viva

Founded in 1999, Viva is etched factoring history and continues to help businesses thrive today. If your company needs working capital to fund growth expenses, cope with slow-paying clients, or manage everyday expenses like payroll, Viva can help. Request a complimentary factoring quote to get started.

- 6 Proven Customer Retention Tips to Drive Long-Term Loyalty - June 4, 2025

- 5 Key Traits of a Top Factoring Company (And How Viva Stacks Up) - May 22, 2025

- The Impact of Late Payments: How Factoring Protects SMEs - April 11, 2025